Death in the Kingdom of Pines

Chapter 1

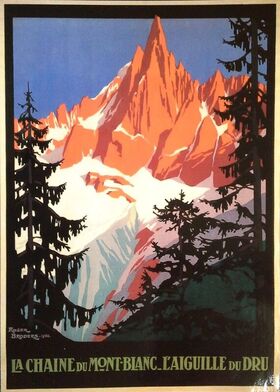

Chamonix, Haute Savoie, France, February 1931

Marie-Laure Monaghan was making her way to work. As she came out of the forest and stopped to put on her skis, excitement rose up in her. “I’m going to work,” she told herself. An icy wind off the glaciers on Mont Blanc hit the back of her neck and she shivered. But as she looked across the valley of white snow and black pines to the towering rocks beyond, she was sure it was going to be a beautiful day.

It was not yet eight o’clock and the sun was still behind the mountain. Below her was a stretch of snow, at the bottom a row of buildings, including a café where glass doors gave on to a small terrace with views up the slope. Beyond the buildings was the road to Chamonix. Until three years ago, this modest hillside had been the field where the pigs were kept. Now it was a ski piste. A nursery slope admittedly, and one crisscrossed with tracks and pitted with holes where gravity had got the better of beginners, but recognisably a piste. It had its part in the unstoppable craze for skiing which was sweeping the French Alps, bringing money and glamour to downtrodden villages, dragging the bemused inhabitants out of their dark chalets and turning the deathly Alpine winter into a season of speed and fun.

And for Marie-Laure, this slope was now her workplace. She buckled on her skis, then hesitated, suddenly aware that anyone in the café would be able to look out and watch her descending. New pupils could be seeing her, their ski instructor, arriving for work. Suppose she fell? Her face burned with the imagined humiliation. It was too early for pupils to have arrived but her fellow instructors might already be there. The thought of them gave her a fierce determination to ski the short slope beautifully. So she did.

At the bottom, she took off her skis and leaned them on the newly-built rack, smelling of fresh pine. She knocked on the glass doors and Pierrot let her in.

The café was quiet. “Where’s Harald?” she asked.

Pierrot shrugged. “Out for a first run I suppose,” he said. “No lessons until half past nine.”

“Actually I’m giving an early morning lesson,” Marie-Laure announced.

Pierrot shrugged again, with what she was sure was a deliberate lack of interest.

“Yes, I’m expecting my client in about fifteen minutes,” she went on. “So can I have a cup of coffee first?”

Pierrot gaped at her. She wasn’t sure if he was being rude or just stupid. Both probably. He was a gangly youth who opened up the café for Harald in the mornings, manned the bar at night and helped out with ski lessons during the day. He wasn’t exactly an instructor, in her view.

“You want some coffee?” he said. “I thought you English girls drank tea.”

“I’m not English,” she said firmly. “We’ve been through this already.”

She sipped the coffee, looked out at the snow and waited for God’s Gift. The clock ticked to 8.15. 8.20. He was late.

“Your pupil’s late,” Pierrot said, helpfully. “Who is it anyway?”

“Monsieur Siebert. Um, quite a loud man…” Marie-Laure searched for words to describe him without sounding ungracious. What if he was a balding show-off who fancied himself as God’s Gift to Women and had pinched her bottom when he booked the lesson? A paying pupil was a good pupil.

“The pushy poseur with the big moustache?” Pierrot suggested. “He’s probably still in bed with a hangover. If it’s the bloke I’m thinking of, he was in here till past midnight last night, completely legless.”

Marie-Laure’s heart sank. That sounded like her man.

The Café des Sports was quiet in the first rays of sunlight. It was an old-fashioned place, with a tiled floor and hard metal chairs. The café took up one corner of a plain, square building which fronted on the main road. Once, it had been the Bar des Houches, where men in blue overalls sat over their red wine and women never crossed the threshold. But three years ago it had been bought by the famous ski champion Harald Sigursson, renamed the Café des Sports and turned into the hub of his ski school.

There was a rush of cold air as the door opened and Harald entered, vigorous and in a good mood from his morning run. But his expression darkened as he looked around the café.

“Where is everybody?” he demanded.

“Jean-Luc is giving an early lesson,” Pierrot said.

“And Raymond?”

“Er, Raymond is…” At that moment the front door opened and a bulky figure came in.

“…Late!” barked Harald.

Raymond took off his coat and offered no apology, just settling himself on a stool at the bar. Pierrot sniggered, like a naughty schoolboy protected by his bigger friend. Harald was prevented from saying more as the front door opened again and five men entered, carrying skis and dressed in tweeds and thick jerseys. Harald took them over to his office – a designated table in one corner of the bar. Marie-Laure knew he was giving them his usual introductory talk on the benefits of the Harald Sigursson ski tuition method.

“Not working this morning Marie-Laure?” asked Raymond.

“She’s waiting for her pupil,” said Pierrot.

“Oh yes, your rich guy,” said Raymond. “He hasn’t turned up? What a shame. Maybe he’s not happy with the, er, service he’s getting from you. Maybe you should have given him what he wanted.”

Marie-Laure sat stony-faced.

“Maybe she did give him what he wanted,” said Pierrot gleefully. “And now he doesn’t need to bother with a ski lesson just to get a poke.”

“What was he like then Marie-Laure?” Raymond persisted. “Big bloke is he?”

“I wouldn’t know,” she said, trying to sound as neutral as possible.

“Come on,” said Raymond. “You’re not at the convent now. You won’t get pupils by acting like a nun.”

She wasn’t going to rise to this. “He’s just late,” she said.

“Oh well, of course, He was planning to do a warm-up run before he had his lesson with you,” Raymond said casually. “Yeh – didn’t he tell you? He mentioned it when we were chatting at the bar last night. I told him to drop into the P’tit Alpe while he was up there. You know Old Pascal is selling his pear brandy from behind the cowshed now. Just the thing to get you going in the morning.”

Suddenly Harald was there. “Enough!” he snapped at Raymond and Pierrot. “I’ve got clients here expecting to start their morning’s lesson. Now get going. My ski school has a reputation to maintain.”

“We haven’t finished our coffee…” Pierrot whined.

“Fuck off out of here!”

They did.

Once again the bar was quiet. “Idiots,” sighed Harald. “And why are you still here Marie-Laure?” She explained again that her pupil, Monsieur Siebert, had not turned up.

“But I saw him,” Harald said. “An hour ago – more. He was heading this way, carrying his skis. Said he’d booked an early lesson and was going up the mountain road for a practice run first.”

Marie-Laure looked out at the slopes. “I’ll go and find him. He might have got lost.” She got up and reached for her jersey.

“Surely he can look after himself,” said Harald. “He told me he’d been a telemark champion in the Jura and was just coming to us for a little refresher course.”

“He told me that too. But in truth he can barely stand up on his skis,” she said. “I’d better go.”

“Yes you’d better go,” Harald said grimly. “If he breaks a leg he might not pay.”

She picked her skis off the rack. At nearly two metres, they were much taller than her. Catching sight of her reflection in the café window, she considered the effect, with dissatisfaction. The top half wasn’t too bad: her dark bobbed hair, together with the sunglasses, created an effect worthy of Coco Chanel and down to her neat waist she looked rather gamine, she thought. But there was no disguising her unfashionably round hips and lamentably un-coltish legs. God’s Gift to Women had made a pass at her after the first lesson. But then he probably made a pass at anyone under the age of 50 who didn’t actually have to shave in the morning.

She looked up. A figure had appeared out of the trees at the top of the nursery slope. Normally this slope was her domain, where she was either persuading nervous newcomers to point their skis downhill and slide a little way – just a little way – or else discouraging over-confident speed-seekers from zooming straight down and right through the windows of the Café des Sports.

Was it Monsieur Siebert, at last? But no, this was an expert skier, zigzagging casually, followed by two knock-kneed shapes descending very slowly. Her stomach did a somersault. It was Jean-Luc. But she was going to stay calm.

Instead of setting off, she waited until Jean-Luc glided to a halt in front of her. “Not working this morning Marie-Laure?” he said. His sarcastic grin attracted and repelled her, as ever.

“Shouldn’t you be helping them?” she asked, indicating his two charges, one of whom was now flailing around on the ground while the other tried to help him up with a ski pole.

Jean-Luc threw them a glance. “They learn more when they make their own mistakes,” he said. “Couldn’t Harald find you a pupil this morning? You can’t be a ski instructor without pupils Marie-Laure.”

“Actually I have a pupil. Monsieur Siebert.”

“The pushy poseur with the big moustache?”

“That’s the one. He booked an early lesson but hasn’t turned up. Apparently he went out for a warm-up run.”

“Yes – we saw him,” Jean-Luc said.

She sighed. Everybody had seen him except her, his instructor.

“Where exactly did you see him?”

“At the top of the road.”

“Was he alright?” she asked.

“His technique was rubbish but I didn’t stop to criticise. I assumed he was going to do what we did and ski back down the track. We stopped quite a few times so I expected him to overtake us, but he didn’t.”

Marie-Laure sighed again. “I think he’s getting stuck into the pear brandies.” She put on her gloves.

“Let me dump these two and I’ll come with you,” Jean-Luc said. His pupils had collapsed in a heap, their glasses steamed up and a faint mumbling coming from their mouths.

“No thanks,” Marie-Laure said crisply. “You really ought to go over a few basics with them.”

She did not want Jean-Luc around; she didn’t need him. What there had been between them was over and that was how she wanted it. And really there had been nothing between them. She did not care about Jean-Luc one way or the other. She repeated this to herself a few times.

Marie-Laure shouldered her skis and set off along the track, which in summer was a dirt road leading up to Old Pascal’s farm, the P’tit Alpe. She liked walking. Her leather boots, though heavy, gripped the snow well and her Norwegian ash skis – they had to be ash, Harald insisted – were light to carry.

Among the trees, she inhaled the scent of pine, the perfumed breath of the mountain, and felt the rush it always gave her. Her feet crunched in fresh snow. Shafts of sunlight filtered through the trees and touched her eyes. It was a glorious day.

She still felt surprised that this was a Wednesday, in February, and she was out in the forest instead of in the classroom at the Ecole de Sainte Thérèse de la Petite Fleur, teaching English grammar to Junior Four. A background feeling that she should be at work nagged her. But she was at work – she was a ski instructor now. The convent school was behind her. She had a wonderful new job.

But would it stay wonderful if she made a mess of this? If she discovered God’s Gift sitting over a bottle of poire at the P’tit Alpe and he told her to get lost. What the hell made her think he was going to pay a woman to teach him when he could ski perfectly well, as everyone could see…

Well, Harald would back her up. Nobody argued with Harald. Tall, lean, his dark hair grey now, his fierce brows and hooked nose giving him the air of a brooding eagle, he barked orders in his Norwegian-accented French and his pupils obeyed without question. Nobody argued with Harald’s three international gold medals in ski jumping and two in long distance ski racing.

As she walked up the road, she could see tracks, but apparently only of one skier. Jean-Luc and his pair of pupils had turned off on to the nursery slope, rather than follow the road all the way down to the village. Had Monsieur Siebert simply given up and gone back to his hotel, without bothering to call into the café? Was he so disappointed with his lesson, or with her?

The road zigzagged uphill and she began to feel warm, even though by now she was completely in the shade of the trees and could barely see the sun. The ground was treacherous: every now and then she slipped on a patch of ice. Tracks showed that various skiers had come down this way, this morning or some time before.

Damn Monsieur Siebert! She should never have gone near the arrogant boor. But he was ready to pay good money and he was her first real client, as she saw it. Rather than just being a pupil handed to her by Harald or one of the other instructors, Monsieur Siebert had driven up to the ski school in his sports car, asking for her – the lady ski instructor. Jean-Luc and the others had sniggered but she knew they were envious. Up till then they had tolerated her as useful for taking the kind of pupils they didn’t want to teach. “Nervous types,” Jean-Luc had said. “Little kids, spinsters.” The sort who wouldn’t tip. The sort who were not seeking Harald’s rugged glamour or Jean-Luc’s practised charm or Raymond and Pierrot’s… what exactly did Raymond and Pierrot have to offer, she wondered? They were local lads, “strong boys who know these mountains,” Harald said approvingly. When she had landed God’s Gift, with his swagger and ready cash, they had been seething.

It had not taken her long to realise that Joseph Siebert had only requested her because he didn’t want the male instructors to see that he wasn’t as good a skier as he claimed. Marie-Laure was used to men with a high opinion of themselves. Didn’t she have three older brothers? Their teasing, mockery and put-downs had always provoked a reaction in the pit of her stomach, a fiery ball of determination not to be beaten. Monsieur Siebert, Jean-Luc and his fellow instructors all provoked the same feeling and a silent vow formed in her head: “This job is my way out and I’m not going to let you stop me.”

Boys had to be told they were the best, she knew. Each one of her brothers was somehow their mother’s favourite. “There’s nothing better than my boys,” Mam had always said. “I know they’ll look after me.” She had carried on saying that, even when it was painfully untrue. Still, one of the brothers was still at home, Marie-Laure reflected, looking after Mam, which was more than she was doing herself. The daily guilt about leaving Dublin twanged in her mind.

It was true that the previous day’s lesson with God’s Gift to Women had not gone well. He refused to admit to his inexperience and listen to her teaching; in fact, he had trouble acknowledging that he was the pupil and she the tutor. She had feared he might call a halt to the classes and she would lose the 200 francs, so she had reined in her advice, to bolster his pride and keep him sweet. “Just like any silly woman,” she told herself. She had given him the illusion that he was a better skier than he was, and now he had headed off alone. She knew that he would have seen himself emerging triumphantly on to the nursery slope, executing a few expert turns, before stopping in front of her in a spray of snow.

But if that was his plan, he should have been basking in her admiration an hour ago.

Climbing the next hairpin bend, she could see something lying across the road at the corner ahead. Something straight. A ski. Cold fear clutched her guts. There was trouble now. The fool had got drunk on pear brandy and crashed into a tree: just the thing to happen on this icy path.

She began to run. “I’m coming,” she called. No reply. Either he had knocked himself out or was weak with pain from a broken leg.

She could see him now, lying on his back, among the pines at the side of the road. As she got closer, she thought how awkwardly he was lying. How uncomfortable he must be. Before she reached him, she knew. She had seen a dead person before.

Marie-Laure put her skis down and looked at him. A Hail Mary ran automatically through her mind.

The bastard. What kind of idiot skis into a tree and breaks his neck on a sunny morning?

He was lying with his legs half on the road, one ski still on, his body under the trees. She clambered through the deep snow to his head. And stopped.

It was not a broken neck that had killed him. He lay in a halo of blood, puddles of red staining the white all around him. Even the fallen pine cones were red. One of his bamboo ski poles had been driven through his throat.

Chapter 1

Chamonix, Haute Savoie, France, February 1931

Marie-Laure Monaghan was making her way to work. As she came out of the forest and stopped to put on her skis, excitement rose up in her. “I’m going to work,” she told herself. An icy wind off the glaciers on Mont Blanc hit the back of her neck and she shivered. But as she looked across the valley of white snow and black pines to the towering rocks beyond, she was sure it was going to be a beautiful day.

It was not yet eight o’clock and the sun was still behind the mountain. Below her was a stretch of snow, at the bottom a row of buildings, including a café where glass doors gave on to a small terrace with views up the slope. Beyond the buildings was the road to Chamonix. Until three years ago, this modest hillside had been the field where the pigs were kept. Now it was a ski piste. A nursery slope admittedly, and one crisscrossed with tracks and pitted with holes where gravity had got the better of beginners, but recognisably a piste. It had its part in the unstoppable craze for skiing which was sweeping the French Alps, bringing money and glamour to downtrodden villages, dragging the bemused inhabitants out of their dark chalets and turning the deathly Alpine winter into a season of speed and fun.

And for Marie-Laure, this slope was now her workplace. She buckled on her skis, then hesitated, suddenly aware that anyone in the café would be able to look out and watch her descending. New pupils could be seeing her, their ski instructor, arriving for work. Suppose she fell? Her face burned with the imagined humiliation. It was too early for pupils to have arrived but her fellow instructors might already be there. The thought of them gave her a fierce determination to ski the short slope beautifully. So she did.

At the bottom, she took off her skis and leaned them on the newly-built rack, smelling of fresh pine. She knocked on the glass doors and Pierrot let her in.

The café was quiet. “Where’s Harald?” she asked.

Pierrot shrugged. “Out for a first run I suppose,” he said. “No lessons until half past nine.”

“Actually I’m giving an early morning lesson,” Marie-Laure announced.

Pierrot shrugged again, with what she was sure was a deliberate lack of interest.

“Yes, I’m expecting my client in about fifteen minutes,” she went on. “So can I have a cup of coffee first?”

Pierrot gaped at her. She wasn’t sure if he was being rude or just stupid. Both probably. He was a gangly youth who opened up the café for Harald in the mornings, manned the bar at night and helped out with ski lessons during the day. He wasn’t exactly an instructor, in her view.

“You want some coffee?” he said. “I thought you English girls drank tea.”

“I’m not English,” she said firmly. “We’ve been through this already.”

She sipped the coffee, looked out at the snow and waited for God’s Gift. The clock ticked to 8.15. 8.20. He was late.

“Your pupil’s late,” Pierrot said, helpfully. “Who is it anyway?”

“Monsieur Siebert. Um, quite a loud man…” Marie-Laure searched for words to describe him without sounding ungracious. What if he was a balding show-off who fancied himself as God’s Gift to Women and had pinched her bottom when he booked the lesson? A paying pupil was a good pupil.

“The pushy poseur with the big moustache?” Pierrot suggested. “He’s probably still in bed with a hangover. If it’s the bloke I’m thinking of, he was in here till past midnight last night, completely legless.”

Marie-Laure’s heart sank. That sounded like her man.

The Café des Sports was quiet in the first rays of sunlight. It was an old-fashioned place, with a tiled floor and hard metal chairs. The café took up one corner of a plain, square building which fronted on the main road. Once, it had been the Bar des Houches, where men in blue overalls sat over their red wine and women never crossed the threshold. But three years ago it had been bought by the famous ski champion Harald Sigursson, renamed the Café des Sports and turned into the hub of his ski school.

There was a rush of cold air as the door opened and Harald entered, vigorous and in a good mood from his morning run. But his expression darkened as he looked around the café.

“Where is everybody?” he demanded.

“Jean-Luc is giving an early lesson,” Pierrot said.

“And Raymond?”

“Er, Raymond is…” At that moment the front door opened and a bulky figure came in.

“…Late!” barked Harald.

Raymond took off his coat and offered no apology, just settling himself on a stool at the bar. Pierrot sniggered, like a naughty schoolboy protected by his bigger friend. Harald was prevented from saying more as the front door opened again and five men entered, carrying skis and dressed in tweeds and thick jerseys. Harald took them over to his office – a designated table in one corner of the bar. Marie-Laure knew he was giving them his usual introductory talk on the benefits of the Harald Sigursson ski tuition method.

“Not working this morning Marie-Laure?” asked Raymond.

“She’s waiting for her pupil,” said Pierrot.

“Oh yes, your rich guy,” said Raymond. “He hasn’t turned up? What a shame. Maybe he’s not happy with the, er, service he’s getting from you. Maybe you should have given him what he wanted.”

Marie-Laure sat stony-faced.

“Maybe she did give him what he wanted,” said Pierrot gleefully. “And now he doesn’t need to bother with a ski lesson just to get a poke.”

“What was he like then Marie-Laure?” Raymond persisted. “Big bloke is he?”

“I wouldn’t know,” she said, trying to sound as neutral as possible.

“Come on,” said Raymond. “You’re not at the convent now. You won’t get pupils by acting like a nun.”

She wasn’t going to rise to this. “He’s just late,” she said.

“Oh well, of course, He was planning to do a warm-up run before he had his lesson with you,” Raymond said casually. “Yeh – didn’t he tell you? He mentioned it when we were chatting at the bar last night. I told him to drop into the P’tit Alpe while he was up there. You know Old Pascal is selling his pear brandy from behind the cowshed now. Just the thing to get you going in the morning.”

Suddenly Harald was there. “Enough!” he snapped at Raymond and Pierrot. “I’ve got clients here expecting to start their morning’s lesson. Now get going. My ski school has a reputation to maintain.”

“We haven’t finished our coffee…” Pierrot whined.

“Fuck off out of here!”

They did.

Once again the bar was quiet. “Idiots,” sighed Harald. “And why are you still here Marie-Laure?” She explained again that her pupil, Monsieur Siebert, had not turned up.

“But I saw him,” Harald said. “An hour ago – more. He was heading this way, carrying his skis. Said he’d booked an early lesson and was going up the mountain road for a practice run first.”

Marie-Laure looked out at the slopes. “I’ll go and find him. He might have got lost.” She got up and reached for her jersey.

“Surely he can look after himself,” said Harald. “He told me he’d been a telemark champion in the Jura and was just coming to us for a little refresher course.”

“He told me that too. But in truth he can barely stand up on his skis,” she said. “I’d better go.”

“Yes you’d better go,” Harald said grimly. “If he breaks a leg he might not pay.”

She picked her skis off the rack. At nearly two metres, they were much taller than her. Catching sight of her reflection in the café window, she considered the effect, with dissatisfaction. The top half wasn’t too bad: her dark bobbed hair, together with the sunglasses, created an effect worthy of Coco Chanel and down to her neat waist she looked rather gamine, she thought. But there was no disguising her unfashionably round hips and lamentably un-coltish legs. God’s Gift to Women had made a pass at her after the first lesson. But then he probably made a pass at anyone under the age of 50 who didn’t actually have to shave in the morning.

She looked up. A figure had appeared out of the trees at the top of the nursery slope. Normally this slope was her domain, where she was either persuading nervous newcomers to point their skis downhill and slide a little way – just a little way – or else discouraging over-confident speed-seekers from zooming straight down and right through the windows of the Café des Sports.

Was it Monsieur Siebert, at last? But no, this was an expert skier, zigzagging casually, followed by two knock-kneed shapes descending very slowly. Her stomach did a somersault. It was Jean-Luc. But she was going to stay calm.

Instead of setting off, she waited until Jean-Luc glided to a halt in front of her. “Not working this morning Marie-Laure?” he said. His sarcastic grin attracted and repelled her, as ever.

“Shouldn’t you be helping them?” she asked, indicating his two charges, one of whom was now flailing around on the ground while the other tried to help him up with a ski pole.

Jean-Luc threw them a glance. “They learn more when they make their own mistakes,” he said. “Couldn’t Harald find you a pupil this morning? You can’t be a ski instructor without pupils Marie-Laure.”

“Actually I have a pupil. Monsieur Siebert.”

“The pushy poseur with the big moustache?”

“That’s the one. He booked an early lesson but hasn’t turned up. Apparently he went out for a warm-up run.”

“Yes – we saw him,” Jean-Luc said.

She sighed. Everybody had seen him except her, his instructor.

“Where exactly did you see him?”

“At the top of the road.”

“Was he alright?” she asked.

“His technique was rubbish but I didn’t stop to criticise. I assumed he was going to do what we did and ski back down the track. We stopped quite a few times so I expected him to overtake us, but he didn’t.”

Marie-Laure sighed again. “I think he’s getting stuck into the pear brandies.” She put on her gloves.

“Let me dump these two and I’ll come with you,” Jean-Luc said. His pupils had collapsed in a heap, their glasses steamed up and a faint mumbling coming from their mouths.

“No thanks,” Marie-Laure said crisply. “You really ought to go over a few basics with them.”

She did not want Jean-Luc around; she didn’t need him. What there had been between them was over and that was how she wanted it. And really there had been nothing between them. She did not care about Jean-Luc one way or the other. She repeated this to herself a few times.

Marie-Laure shouldered her skis and set off along the track, which in summer was a dirt road leading up to Old Pascal’s farm, the P’tit Alpe. She liked walking. Her leather boots, though heavy, gripped the snow well and her Norwegian ash skis – they had to be ash, Harald insisted – were light to carry.

Among the trees, she inhaled the scent of pine, the perfumed breath of the mountain, and felt the rush it always gave her. Her feet crunched in fresh snow. Shafts of sunlight filtered through the trees and touched her eyes. It was a glorious day.

She still felt surprised that this was a Wednesday, in February, and she was out in the forest instead of in the classroom at the Ecole de Sainte Thérèse de la Petite Fleur, teaching English grammar to Junior Four. A background feeling that she should be at work nagged her. But she was at work – she was a ski instructor now. The convent school was behind her. She had a wonderful new job.

But would it stay wonderful if she made a mess of this? If she discovered God’s Gift sitting over a bottle of poire at the P’tit Alpe and he told her to get lost. What the hell made her think he was going to pay a woman to teach him when he could ski perfectly well, as everyone could see…

Well, Harald would back her up. Nobody argued with Harald. Tall, lean, his dark hair grey now, his fierce brows and hooked nose giving him the air of a brooding eagle, he barked orders in his Norwegian-accented French and his pupils obeyed without question. Nobody argued with Harald’s three international gold medals in ski jumping and two in long distance ski racing.

As she walked up the road, she could see tracks, but apparently only of one skier. Jean-Luc and his pair of pupils had turned off on to the nursery slope, rather than follow the road all the way down to the village. Had Monsieur Siebert simply given up and gone back to his hotel, without bothering to call into the café? Was he so disappointed with his lesson, or with her?

The road zigzagged uphill and she began to feel warm, even though by now she was completely in the shade of the trees and could barely see the sun. The ground was treacherous: every now and then she slipped on a patch of ice. Tracks showed that various skiers had come down this way, this morning or some time before.

Damn Monsieur Siebert! She should never have gone near the arrogant boor. But he was ready to pay good money and he was her first real client, as she saw it. Rather than just being a pupil handed to her by Harald or one of the other instructors, Monsieur Siebert had driven up to the ski school in his sports car, asking for her – the lady ski instructor. Jean-Luc and the others had sniggered but she knew they were envious. Up till then they had tolerated her as useful for taking the kind of pupils they didn’t want to teach. “Nervous types,” Jean-Luc had said. “Little kids, spinsters.” The sort who wouldn’t tip. The sort who were not seeking Harald’s rugged glamour or Jean-Luc’s practised charm or Raymond and Pierrot’s… what exactly did Raymond and Pierrot have to offer, she wondered? They were local lads, “strong boys who know these mountains,” Harald said approvingly. When she had landed God’s Gift, with his swagger and ready cash, they had been seething.

It had not taken her long to realise that Joseph Siebert had only requested her because he didn’t want the male instructors to see that he wasn’t as good a skier as he claimed. Marie-Laure was used to men with a high opinion of themselves. Didn’t she have three older brothers? Their teasing, mockery and put-downs had always provoked a reaction in the pit of her stomach, a fiery ball of determination not to be beaten. Monsieur Siebert, Jean-Luc and his fellow instructors all provoked the same feeling and a silent vow formed in her head: “This job is my way out and I’m not going to let you stop me.”

Boys had to be told they were the best, she knew. Each one of her brothers was somehow their mother’s favourite. “There’s nothing better than my boys,” Mam had always said. “I know they’ll look after me.” She had carried on saying that, even when it was painfully untrue. Still, one of the brothers was still at home, Marie-Laure reflected, looking after Mam, which was more than she was doing herself. The daily guilt about leaving Dublin twanged in her mind.

It was true that the previous day’s lesson with God’s Gift to Women had not gone well. He refused to admit to his inexperience and listen to her teaching; in fact, he had trouble acknowledging that he was the pupil and she the tutor. She had feared he might call a halt to the classes and she would lose the 200 francs, so she had reined in her advice, to bolster his pride and keep him sweet. “Just like any silly woman,” she told herself. She had given him the illusion that he was a better skier than he was, and now he had headed off alone. She knew that he would have seen himself emerging triumphantly on to the nursery slope, executing a few expert turns, before stopping in front of her in a spray of snow.

But if that was his plan, he should have been basking in her admiration an hour ago.

Climbing the next hairpin bend, she could see something lying across the road at the corner ahead. Something straight. A ski. Cold fear clutched her guts. There was trouble now. The fool had got drunk on pear brandy and crashed into a tree: just the thing to happen on this icy path.

She began to run. “I’m coming,” she called. No reply. Either he had knocked himself out or was weak with pain from a broken leg.

She could see him now, lying on his back, among the pines at the side of the road. As she got closer, she thought how awkwardly he was lying. How uncomfortable he must be. Before she reached him, she knew. She had seen a dead person before.

Marie-Laure put her skis down and looked at him. A Hail Mary ran automatically through her mind.

The bastard. What kind of idiot skis into a tree and breaks his neck on a sunny morning?

He was lying with his legs half on the road, one ski still on, his body under the trees. She clambered through the deep snow to his head. And stopped.

It was not a broken neck that had killed him. He lay in a halo of blood, puddles of red staining the white all around him. Even the fallen pine cones were red. One of his bamboo ski poles had been driven through his throat.